“More than 50 of us went to Armstrong to pick up transfer applications. But when I realized I was the only one who actually turned it in, I had a choice: either go through with it or go back to Savannah State and forget the whole thing,” said Otis Johnson, on the decision that led him to become the 1st African American graduate of Armstrong Junior College.

In 1963, during the Savannah State College Student Uprising, Johnson joined 65 other Black students from the all-Black Savannah State College in a march to apply for transfer to the then all-white Armstrong Junior College.

Before Johnson’s acceptance, Armstrong had already turned away four Black applicants.

Foreman Hawes, the president of Armstrong Junior College, at the time, addressed the student body in a meeting where Johnson was conspicuously absent.

“When a federal court orders a college to accept a student applicant, that institution loses some degree of control over its admissions—a situation colleges and universities are keen to avoid,” Hawes said.

As Johnson stepped into the newsroom, his presence was immediately felt. Though in his eighties, he stood tall and spoke in a deep, firm tone that commanded the room’s attention.

“I could have said well, nobody else came over, should I go over there into the unknown, because we didn’t know if there would be violence,” Johnson said, his voice unwavering.“A lot of people died in ‘63.”

Breaking Barriers: The Early Years and Activism

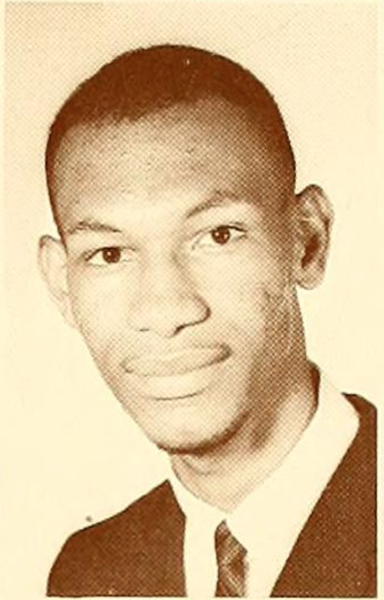

Johnson described his experience at Armstrong as akin to being an “Invisible Man.” In fact, the Inkwell featured no photos of Johnson.

However, desegregating Armstrong wasn’t Johnson’s first foray into activism.

“The Savannah Youth Council was the largest youth council among the NAACP branches in the country,” Johnson said.

“They had good leadership, good mentorship, and so when the sit-ins went down in Tennessee and North Carolina, it wasn’t long before the urge was to say, ‘Hey, you know, we can’t let them beat us.'”

During his senior year of high school, Johnson wasn’t a member of the youth council. Yet, he and some classmates took it upon themselves to march to the police station to protest the arrests of the youth council members.

Reflecting on the experience with a chuckle, Johnson said, “Well, again, I proved my naivete along with a whole lot of others, because we went to school, checked in, and were recorded as present.”

“When we went back to go back to school, we were met by the principal. We didn’t even get in the front door; he met us on the way to the school and said, ‘You are all suspended.'”

The Philosophy of a “Race Man”

Johnson’s early years of activism were just the beginning of a lifelong commitment to racial equality, a commitment he passionately describes as being a “Race Man.”

“You got the race man who says no, my people first, my people always, and whatever I do, I’m going to be doing it to advance my people. Because if my people advance, I advance,” Johnson said with palpable enthusiasm.

This philosophy of being a “Race Man” has been a consistent thread woven throughout Johnson’s life and career. Whether it was establishing the undergraduate program in social work at Savannah State University, a historically Black institution, or becoming Savannah’s second African American mayor, Johnson has consistently worked to uplift his community.

For Johnson, effecting real change goes beyond what he describes as “outside advocacy.”

“They taught us about the inside-outside strategy; outside you have advocates who are making noise, making demands, marching, picketing, doing all that kind of stuff, to draw attention to an issue,” Johnson explained.

“But then you gotta have somebody on the inside. Who can take that issue and make something happen.”

In 1983, Johnson was elected Alderman for Savannah’s District Two, an area that was predominantly Black at the time and continues to be so today.

In his victory speech, he said “The tiger is loose in the jungle now.”

Leading Savannah

Johnson took office as Savannah’s mayor in 2004, succeeding Floyd Adams Jr., the city’s first African American mayor.

This transition was part of a long-term strategy that Johnson, Adams and Robert Robinson had devised as far back as 1983.

Their plan aimed to keep the mayor’s office in the hands of the Black community for at least 16 years.

“We actually talked about it, that there was the possibility that in the near future one of us would be the first black mayor,” Johnson said, recalling the discussions with a smile. “We got it to go on for 20 years, that’s a long time in politics, man, a long time in life.”

In preparation for his mayoral role, Johnson did his homework. He studied the leadership styles of other African American mayors and penned columns on the issues he identified as most pressing for Savannah.

“I wrote three on housing, economic development and crime, which were the major issues of the day at the time,” Johnson said. “They still are the major issues of the day, and they will be for a long time because the city government is captured in a lot of ways by the larger institutional structure of the country.”

Johnson served two terms as mayor (2004-2012), and under his administration, in 2006 he helped champion StepUp Savannah’s Poverty Reduction Initiative.

“Savannah, for many decades, has had at least a 20 percent poverty rate, which translates into one in every five Savannahians living in poverty, and poverty is a debilitating circumstance,” Johnson said.

“In the richest country in the world, people who live in poverty are there because of policies, laws and practices that can be changed to improve their lives,” he added, speaking emphatically.

Before his second term ended, Johnson faced what he described as the most difficult decision of his political career: hiring Rochelle Small-Toney as city manager.

“I said I’m going to break two last ceilings; we’ve never had a female city manager and we’ve never had a Black city manager,” Johnson said.

However, Small-Toney’s tenure was short-lived, lasting only 18 months.

“I was concerned about giving her the opportunity she deserved,” Johnson admitted, with realism. “I couldn’t guarantee her success.”

From Near-Death to Renewed Purpose

One fateful Saturday in April 2006 is forever etched in Johnson’s memory. While attending the National Conference of Black Mayors in Memphis, he suffered a massive heart attack in his hotel room.

“The rumor in town in churches were that I was dead,” Johnson said. “I came very close.”

In retrospect, Johnson attributes his health scare to a series of lifestyle choices.

“I wasn’t eating right, my arteries got clogged and I wasn’t exercising like I should, because I was too busy going to meetings and going to this event and that event,” Johnson lamented.

This brush with mortality led Johnson to reevaluate both his personal life and his mayoral responsibilities. He shifted his focus to what he termed the “important things,” reducing his attendance at meetings and events and becoming more selective with his commitments.

“I had a prognosis of five to ten years and I said, well, now I want this second term,” he said. “And if I want the second term, and I get it, I want to be able to live through this second term.”

This life-altering experience catalyzed the formation of Healthy Savannah in 2007, a volunteer-based organization committed to fostering a culture of health in the city.

“I helped create it to help people in Savannah deal with the fact that lifestyle counts and the fact that we have exceptional levels of diabetes, of strokes, heart attacks, all these things, that with just a little adjustment in your lifestyle, you can avoid,” he said.

The Continuing Journey

As he walked into the newsroom, Johnson greeted me with a pamphlet in hand. “This is for you; you asked me what I’ve been doing,” he said, his voice tinged with eagerness.

The pamphlet detailed his recent role as the Chair of the Racial Equity and Leadership (REAL) Task Force, established in 2020 at the behest of Mayor Van Johnson.

“There are a number of things that history will dig up that I can’t even think of, but that’s the last thing that I’ve been working on,” Johnson mused.

Handpicked to steer the task force, Johnson managed a cadre of 45 volunteers. In 2021, the team unveiled a report spotlighting stark disparities in Savannah’s health, housing and educational sectors.

But the report went beyond mere identification; it offered tangible solutions like bolstering affordable housing and expanding broadband connectivity to address these inequities.

The task force has since splintered into specialized subcommittees, each zeroing in on a particular area of disparity.

In a life marked by breaking barriers and advocating for change, Johnson’s journey comes full circle. His recent work with the (REAL) task force serves as a testament to his enduring commitment to social justice.

“You’re aware of it but then the question is, what do you do about it? The Civil Rights Movement gave me an opportunity to do something about it, to be a part of doing something about it “, said Johnson with his voice imbued with the wisdom of years.

As he reflects on his past and looks toward the future, Johnson remains, above all, a man in motion—always striving, always advocating and always serving his community.

Erica Barner • Sep 22, 2023 at 9:09 pm

Well Spoken Words and Wrote with excellent quality.

Great Job Jabari Gibbs

Linda Gibbs • Sep 22, 2023 at 6:53 pm

It’s always good to hear about others who put there life there education to do what they could to help our black culture through this well written and understandable article I came to learn of a important person. Thank you well written

Reginald Easterling • Sep 22, 2023 at 5:33 pm

Dr Johnson has always been a man of integrity and action. He is a great activist was a great college professor.

I learned a lot from him when I took some of his classes at SSU. HE is a great courageous man. I thank for him.

Sincerely

Reginald Easterling