Hannah Hanlon, Staff Writer

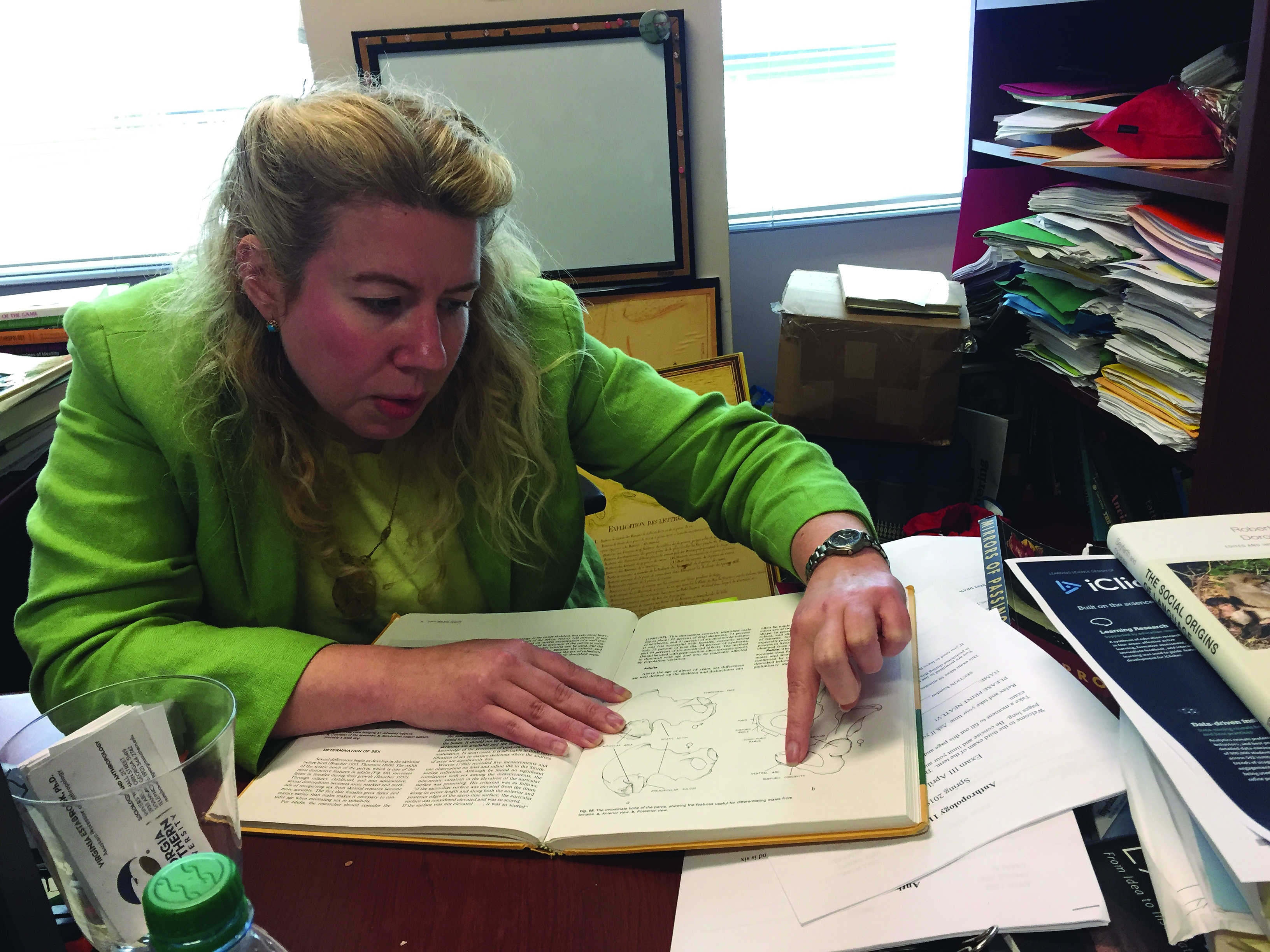

Ever since the Smithsonian Channel documentary about Brigadier General Casimir Pulaski was released on April 8, Dr. Virginia Estabrook, a Georgia Southern anthropology professor, has been fielding phone calls and interview requests from around the world.

“This is not usually my life,” said Estabrook. “It has been crazy!”

The interest and curiosity are understandable.

Pulaski is considered an American Revolutionary War hero and is called the Father of the American Calvary.

As portrayed in the documentary, there was an investigation into the bones that were discovered at the original Pulaski monument on Monterey Square in Savannah.

The suspicion was that the bones were not actually from Pulaski.

The investigation began in 1996 when the monument was in need of repair, and was initially trying to deduce whether there were human remains inside the monument.

Karen Burns, a well-reputed forensic anthropologist, and Chuck Powell, the coordinator for the Pulaski Identification Committee, had the monument opened in 1996. A metal box was found, and inside there were the remains of what appeared to be a complete skeleton.

An examination by Burns ensued.

If the skeleton had looked like the expected skeleton of a man, the investigation would have ended there; yet, the pelvis of the skeletal remains appeared to be female, which raised a plethora of questions.

At the focus of these, was the question that prompted the documentary: were the skeletal remains found inside the monument actually Pulaski’s?

Burns conducted a forensic examination of the skeleton for more than ten years but died in 2012 without finding a definitive answer.

In 2015, Chuck Powell’s daughter, Lisa Powell, approached Estabrook to interest her in joining a new investigation if the skeleton that had been found was Pulaski’s.

“I got involved in all of this because of my student[Powell],” said Estabrook.

“We basically reopened the case files and thought is there anything else we can get from this?”

One of the early goals was to interest other people in trying to extract mitochondrial DNA and to see what technologies existed that would enable conclusive findings.

Their endeavors were successful through a series of genetic research tests done at Lakehead University Paleo-DNA lab in Ontario, Canada. A match was found between DNA extracted from Pulaski’s bones and that of a tooth from Pulaski’s grandniece.

“We know now that this was Pulaski,” said Estabrook.

Now that the first big question was solved, another one was raised: Based on the appearance of the skull and the pelvis, was Pulaski intersex?

“What I saw were bones that looked biologically female,” said Estabrook in the documentary.

The question of whether Pulaski was intersex appears to be unresolved due to the limited understanding of how an intersex condition might be revealed in the analysis of a skeleton.

“We really don’t know how an intersex condition affects skeletal development,” said Estabrook.

“For some of these things, like the skeletal development, we don’t really know what intersex looks like, and there are also a bunch of different ways of being intersex, too, and even in individuals with the same condition, there is some variation.”

Pulaski is unique from an anthropological perspective.

“He never perceived himself as anything other than a man,” said Estabrook.

The explanations for why his skeleton developed the way it did remained to be speculated.

As for the public’s response of the investigation findings, there seems to be more curiosity than negativity.

“This went viral really fast,” said Estabrook. “Within a matter of a couple of days, it was everywhere.”

“Everywhere” included The Chicago Tribune, The New York Times, and BBC, among other national and international news outlets.

Interestingly, there has been little community interest, perhaps because people locally have already known about the Pulaski monument report.

One of the most interesting questions Estabrook has received is “does this rewrite history?”

“On one level, no, Pulaski is Pulaski. What he did does not change,” said Estabrook.

“What does maybe change is that his story becomes relevant to a different group of people than his story was relevant to before.”