The Willow Hill School: A brief history

March 28, 2018

The Beginning

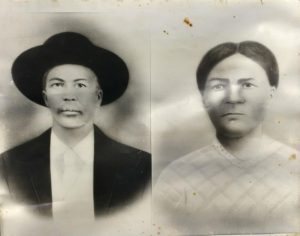

In 1874, nine years after the end of the Civil War, a group of former slaves in Portal, Georgia established a school for their children. By 1999, the Willow Hill School was the longest-running school in Bulloch County.

“Willow Hill School is a really unique story in Bulloch County,” Brent Tharp, director of the Georgia Southern Museum, said. “Five families, African-American families of former slaves, got together and pulled together to start a school for their children.”

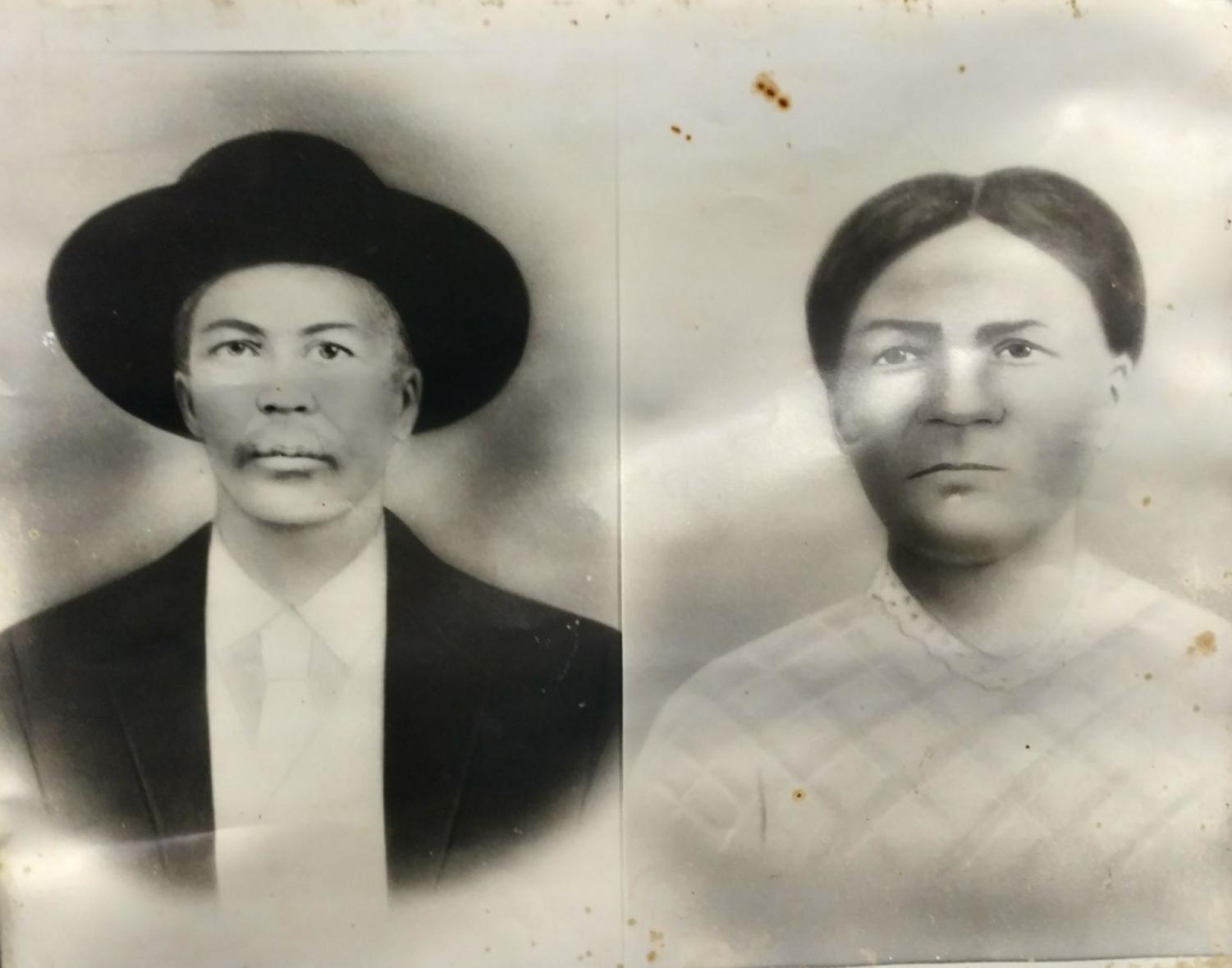

The Parrish, Riggs and Donaldson families were instrumental in establishing the school, according to “Defining Their Destiny: the Story of the Willow Hill School” by former GS faculty member Erik Brooks.

At its beginning, the Willow Hill School took place in an old turpentine shanty, said Dr. Alvin Jackson, president of the Willow Hill Board, family physician and Portal native. The one-room school had few resources at its disposal, including a dictionary and a Bible, meeting for just a few months at a time.

“They hired a teacher who was a former slave who could read and write, and it all started in a turpentine shanty, really just a work barn, that they established as a school very near where the current school is today,” Tharp said.

Georgianna Riggs was only 15 years old when she became the first teacher at the school. A former slave, she learned to read and write during a time when African-Americans were outlawed from education. According to “Defining Their Destiny,” she may have learned to read as a child from the slave owner’s children, or perhaps she was educated at one of the underground schools in the area.

Riggs took the lead in establishing the curriculum, according to “Defining Their Destiny,” teaching the children basic literacy, arithmetic and bible-reading. The school itself was named after Willie Riggs, another member of the Riggs family, who later graduated from Morehouse College in 1894 and returned to teach at Willow Hill.

The Willow Hill School would continue to use the turpentine shanty for the next sixteen years before moving other buildings, according to GS’s Willow Hill Heritage and Renaissance Center Digital Archive Collection project.

Into the early 20th century

By the turn of the century, the Willow Hill School had moved into two buildings near its present site. The school had grown rapidly, providing education through the seventh grade, according to an exhibit at the Willow Hill Heritage and Renaissance Center.

The Rosenwald Fund – established by Julius Rosenwald, part-owner of Sears, Roebuck and Company – provided funds for a third Willow Hill School building in 1914, which lasted until 1941 when a new building was constructed, according to the exhibit. However, as donations from the community became harder to come by, the school’s independence from the Bulloch County Board of Education was jeopardized, according to the GS archive project.

“By the 1920s, for 18 dollars, the Bulloch County school system bought the school at that point in time to establish it, and it got folded into the county school system as a black school,” Tharp said.

Though Moses Parrish, chairman of the Board of Trustees of Willow Hill, had feared that the white board of education would cause educational value at the school to regress, a provision of the sale required that Bulloch County allow the board of trustees to continue in the operation and running of the school, though in a diminished capacity, according to the GS archive project.

From the 1920s through the 1940s, the Willow Hill School campus expanded to provide night school, teacher development, a home economics building and an agriculture building. In 1942, a fifth building was constructed and named the Rosenwald Building.

The 1946 Primary Election

Before the March 6, 1946 Primary Election, African-American citizens in the Willow Hill community had not voted in an election since the 19th century, according to the exhibit.

The night before the election, members of the Willow Hill community met at the Willow Hill school to discuss voting the next day. Outside, the Ku Klux Klan burned a cross as an act of intimidation, according to the exhibit.

“Under the leadership of James Garfield Hall, the third chairman of the Board of Trustees, the citizens voted for the first time since the early 1890s,” reads the text at the exhibit.

From 1954 onward

Until the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling, the Willow Hill School continued much like it had been throughout the early 20th century, according to the GS archive project. The Bulloch County Board of Education, around the time of the decision, built several new schools for African-American students, including the building at Willow Hill, according to the exhibit.

“The building that you see there today was built in 1954, what’s known as an ‘equalization school.’ In an effort to stave off integration, people… built schools to truly look like equal, but separate education – it never was [equal], it was a facade – so that building was built to that, so it has a history of that as well,” Tharp said. “It continued to serve as a school into the 20th century, and ultimately, it became the longest-operating school, black or white, in Bulloch County.”

The 1954 building marked the sixth and final Willow Hill building. A modern facility with indoor plumbing, electricity and telephone service, Willow Hill temporarily closed in 1969 and reopened as an integrated elementary school in 1971, according to the GS archive project.

In 1999, the Willow Hill School closed, reopening briefly as the Portal Willow Hill Community Development Center, according to the exhibit.

When Bulloch County auctioned the property in 2005, descendants of the school founders purchased the school and founded the Willow Hill Heritage and Renaissance Center.

In his book, Brooks quotes Willow Hill board member Dr. Nkenge Jackson: “It was the dreams of these former slaves that were carried through a spirit of yearning for an opportunity to define themselves beyond the barriers of their time. A small one-room school house unnoticed, and trampled by adversity, germinated into a legacy of education, perseverance, family and community and an opportunity to define their destiny.”

Blakeley Bartee, The George-Anne Features Editor, gaartsandent@georgiasouthern.edu