Georgia Southern’s Road Toward Integration

January 20, 2015

In 1941, a lot of things were different. What is now Georgia Southern University was then known as Georgia Teacher’s College (GTC), Martin Luther King Jr. was still in grade school and segregation was alive and well in the south.

Former GTC president Marvin Pittman was fired from his position at the college for, among other charges, allegedly supporting racial integration after he invited George Washington Carver and several other teachers from historically black Tuskegee University to visit the school. Pittman was accused of allowing black teachers to guest lecture in classes and eat in the school cafeteria with white students.

According to a manuscript made by alumni in memory of Pittman, the former-president went on WSB-Radio to respond to the charges against him.

“I do not need to defend myself on the race issue. I am a Southerner by birth and rearing,” Pittman said, according to the document. “I am the grandson of a slave owner, the son of a Confederate soldier. I have the same attitude on that question as has every other intelligent, right-spirited Southern white man.”

Brown v. Board of Education

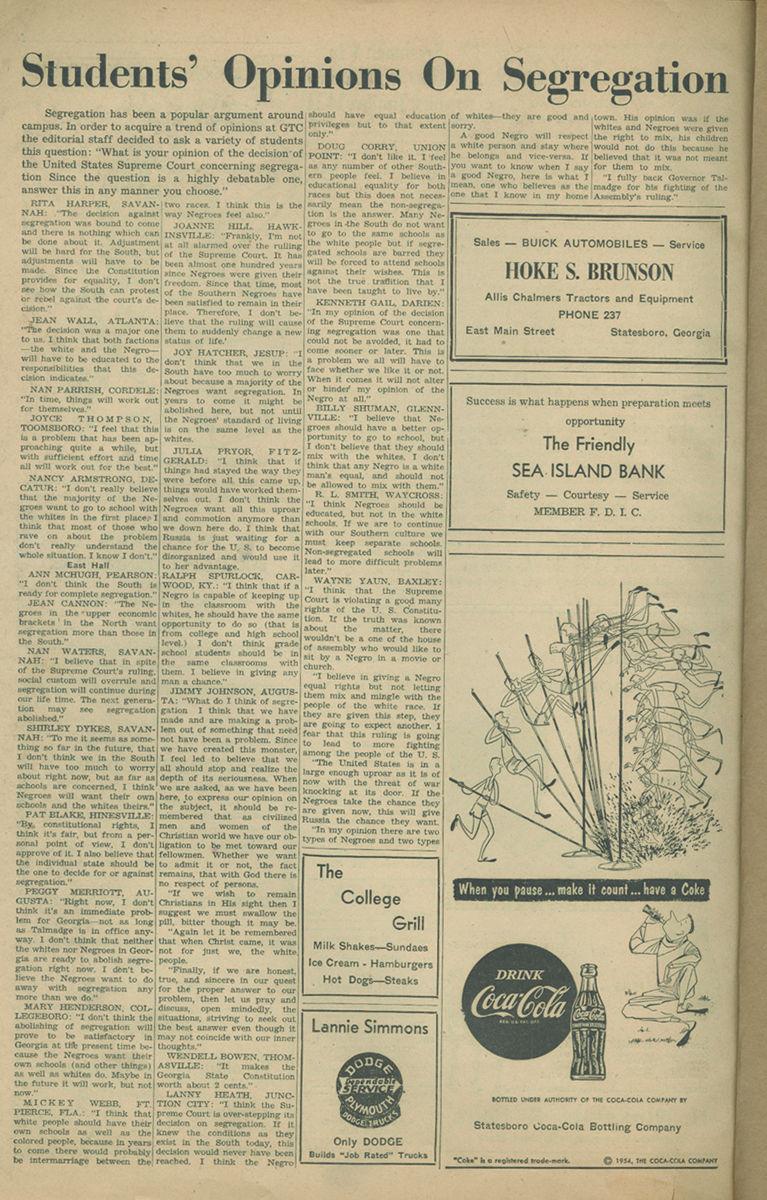

After the Supreme Court ruled segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional in 1954, the editorial staff of The George-Anne asked students to write in with their opinions on the decision.

The response was largely disapproving. Only two of the 25 students published were openly supportive of the ruling.

“Adjustment will be hard for the South, but adjustments will have to be made. Since the Constitution provides for equality, I don’t see how the South can protest or rebel against the court’s decision,” Rita Harper, a student from Savannah, wrote.

Jimmy Johnson, a student from Augusta, provided a religious argument for integration.

“As civilized men and women of the Christian world we have our obligation to be met toward our fellow men,” Johnson wrote. “If we wish to remain Christians in His sight, then I suggest we must swallow the pill, bitter though it may be.”

Other students, however, were openly upset with the ruling. Wayne Yaun, a student from Baxley, wrote in expressing his disapproval of the ruling and said that others agreed with him.

“I think that the Supreme Court is violating a good many rights of the U.S. Constitution. If the truth was known about the matter, there wouldn’t be a one of the house of assembly who would like to sit by a Negro in a movie or church,” Yaun wrote. “I believe in giving a Negro equal rights, but not letting them mix and mingle with the people of the white race. If they are given this step, they are going to expect another.”

However, the most common thread among many of the students who responded to The George-Anne’s call was disbelief that the Supreme Court’s ruling would make any difference in their lives.

“Frankly, I’m not at all alarmed of the ruling of the Supreme Court. It had been almost one hundred years since Negroes were given their freedom. Since that time, most of the Southern Negroes have been satisfied to remain in their place,” wrote Joanne Hill, a student from Hawkinsville. “Therefore, I don’t believe that the ruling will cause them to suddenly change [to] a new status of life.”

Integration

It was 11 years before the first black student would enroll at what was by then known as Georgia Southern College (GSC). In the winter quarter of 1965, two months before King would lead the historic march from Selma to Montgomery, John Bradley enrolled in classes at GSC.

Bradley had already obtained a bachelor’s degree from the historically black Texas Southern University, but needed to take several courses in order to be certified to teach in Georgia. Then-president Zach Henderson greeted Bradley outside of Hanner Gym, and helped him through the registration process.

When integration did occur, neither The George-Anne or The Statesboro Herald made any mention of it.

That fall, six more black students enrolled. One of them, Jessie Ziegler (now Carter), became the first black woman to complete all four years of her education at the college.

“I was proud to be at Georgia Southern. I was proud to be a student there,” Carter said. “I was proud to be able to go to school in my hometown and I was excited, elated and ecstatic about the fact that I was able to go to school.”

Carter said her experience was largely a good one, and that she didn’t experience any of the hostility that some of her black classmates sometimes felt.

“I knew it was the height of the civil rights movement, and I didn’t expect everyone to be friendly, falling all over me, but nevertheless, they were not hostile either,” Carter said. “Everybody treated me with respect.”

In his book, Pursuing a Promise: A History of African-Americans at Georgia Southern University, former GSU professor F. Erik Brooks interviewed Carolyn Hobbs, a black student who enrolled at GSC a few semesters after Carter.

Hobbs described her experience at GSC as largely a good one, but said she also experienced discrimination, from professors as well as students.

“One of my English professors would not call on me when I raised my hand in class. This professor would not meet with me to discuss my tests and assignments with me after class,” Hobbs said. “Other professors, who called roll, they would call my name but would not look at me.”

Despite making integration history at Georgia Southern, Carter said the hardest part of her time in college was making the grades and the most rewarding part was finally making it through.

“Just being able to receive that diploma after four years,” Carter said. “Just being able to walk down the aisle, walk the aisle with my parents there cheering me on and my family members, you know, that was just really the highlight of my experience.”

Carter went on to become a schoolteacher in Treutlen County. She retired in 2000, but still substitute teaches, and tries to use her experience to motivate her students.

“I encourage students every day,” Carter said. “If I did it 50 years ago, you can do it now . . . if I did it then, just think what you can do now.”