Confronting the stigma: A review of domestic and sexual violence on GS’s Campus

April 26, 2018

One in five women and one in 16 men are sexually assaulted while attending college, according to a 2015 report by the National Sexual Violence Resource Center (NSVRC). In addition, the report explains that nearly 90 percent of sexual assault victims do not report the assault.

Here at Georgia Southern University, there have been at least 58 different reports of sexual and domestic crimes to the University Police Department (UPD) since 2012, according to documents obtained by The George-Anne.

These incident reports are mainly comprised of charges of sexual assault, rape, battery, sexual battery and domestic dispute.

In 2015, at least 22 reports of sexual or domestic violence were received by UPD, with 15 of the cases including domestic dispute as either the primary charge or an accompanying charge. The state of Georgia defines domestic violence through the § 19-13-1 Family Violence legal code.

“As used in this article, the term “family violence” means the occurrence of one or more of the following acts between past or present spouses, persons who are parents of the same child, parents and children, stepparents and stepchildren, foster parents and foster children, or other persons living or formerly living in the same household:

(1) Any felony; or

(2) Commission of offenses of battery, simple battery, simple assault, assault, stalking, criminal damage to property, unlawful restraint, or criminal trespass,” according to the GS Annual Security Report.

The Incident Report Process

Over the course of five years, GS UPD has logged over 58 incident reports involving domestic or sexual crimes. UPD Chief Laura McCullough explained that an incident report does not imply guilt but is merely an account of the events the responding officer witnessed.

“The initial incident report is taken by the responding officer, who also conducts the initial investigation. Asking questions and getting information, so that’s what we call the initial investigation,” McCullough said in an interview on April 11. “If the case requires a more extensive investigation, then an investigator will take over as the lead for that investigation.”

McCullough continued to describe the process that unfolds after the initial investigation, saying that a lead investigator may enlist the help of other officers and continues to gather testimonies, physical evidence, video surveillance or any other evidence that may be available. They then compile their findings into a case file.

“[Once the case file is compiled], the determination is made as to how the case proceeds, whether we have enough for some sort of criminal charges being brought or whether we don’t,” McCullough said. “A lot of times, the decision may be that we don’t take any action, because it either doesn’t fall under anything criminal, or we don’t have enough evidence to prove it was something criminal.”

One incident report in this data set initially reported four separate charges that were all dismissed after an investigation was conducted that spanned more than 13 months. The investigation ultimately ended with the accuser being charged with reporting a false crime and false testimony, according to university documents. The NSVRC found in their 2015 report, however, that false reports only make up 2 to 10 percent of total sexual assault crime reports in the U.S.

McCullough mentioned that, while some of their investigations may lead to arrests, others may result in a judicial referral. UPD may also bring criminal cases to prosecuting attorneys, like the state solicitor or the district attorney, to get their input on whether a case is prosecutable.

{{tncms-inline content=”<p>"Even though well intentioned, when a friend makes [a sexual assault report] without the consent of the victim, you&rsquo;re really taking that victim&rsquo;s power away yet again.&rdquo; – Jodi Caldwell, Director of the GS Counseling Center said.</p>” id=”7b99d8a4-bd13-4e7b-941f-e78992ee9adf” style-type=”quote” title=”Jodi Caldwell” type=”relcontent”}}

Reporting Sexual Assault

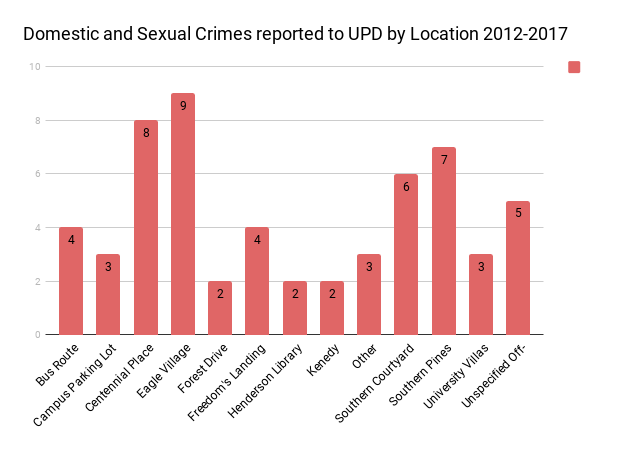

According to incident reports obtained by The George-Anne, the most crimes reported from 2012-2018 occurred in dorms, more specifically lower-class men’s dorms, such as Eagle Village (9) and Centennial Place (8).

Three crimes were alleged to have occurred in campus parking lots, while four were reported to take place on bus routes. Three of the four reports cited incidents of unwanted contact in the fall of 2017, all of which were perpetrated over the course of 11 days.

Victims of sexual assault are offered multiple options when deciding whether to report an assault. Victims always have the option to not report their case to UPD or the university if they don’t wish for the incident to be investigated, according to the GS Counseling Center’s website.

The counseling center’s website also outlines what someone should do if they believe that someone they know may have been the victim of a sexual assault:

-

Always believe them and never blame them for the assault. It is never the victim’s fault.

-

Support the victim’s decisions to report or not report, seek medical services or not seek medical services. It is important that the victim of the assault is in control of their experience.

-

There is no one way to react following a sexual assault. All emotional reactions are within the realm of normal behavior.

-

Offer to stay with the victim to provide support.

Jodi Caldwell, director of the Counseling Center and chair of the Georgia Southern Sexual Assault Response Team, reiterated the importance of being there for a victim of sexual assault, but emphasized that the decision to report should ultimately be left to the victim.

“When somebody has been sexually assaulted, they’ve already had their power taken away from them. Even though well-intentioned, when a friend makes that report without the consent of the victim, you’re really taking that victim’s power away yet again,” Caldwell said in an interview on April 12.

Caldwell went on to explain that the goal of SART is to help the victim begin to feel empowered again. Caldwell also stated that the most helpful thing someone can do for a victim of sexual assault is listen to and believe in them.

Sexual Assault Resources

If you believe that you may be the victim of sexual assault or another related crime, you can contact UPD (912-478-5234), the Counseling Center’s 24-hour crisis intervention hotline (912-478-5541) or visit the Counseling Center’s website to view more sexual assault resources. The website also states the following:

-

If you have experienced sexual assault:

-

It is not your fault.

-

Your choices are valid and valued.

-

All emotional reactions are normal. However you feel is valid and understandable.

-

You are not alone.

-

Self-care is important. Remember to rest, eat, and maintain personal hygiene as best you can during this time.

*Emma Smith and Jozsef Papp contributed to this article.

Ian Leonard, The George-Anne Enterprise Managing Editor, gaspecial@georgiasouthern.edu